There are many aspects of Dungeons and Dragons that have been forgotten, altered, or intentionally removed over the years. THAC0, elves as a character class, and dozens of specific skills have all gone the way of the dinosaurs, and one more staple finds itself in a similar situation, teetering on the edge of abandonment: alignment.

It’s hardly a surprise. Alignment has always been a little bit contentious, especially as applied to entire species or groups within the various settings of the game. Assigning a single set moral alignment to a single person isn’t terribly accurate, much less an entire group of people! But at the same time, alignment chart memes are staples of any online space or fandom, assigning characters into the slots with cute little quotes as examples. Thus, alignment is both underused and ubiquitous in Dungeons and Dragons – as best exemplified by its particular mechanics in 5e. That is to say; it’s there, but it doesn’t actually do anything.

Which is a shame! When used properly, alignment can be a powerful tool for creativity and storytelling, as well as balancing the rules and mechanics of the game. Here’s a brief primer on how.

What is Alignment?

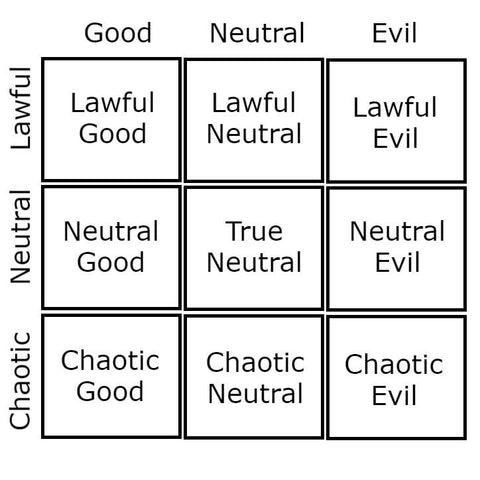

“Alignment” refers to a character’s moral alignment, and generally describes how they are likely to act in any given situation. While many tabletop games use different systems, DnD in particular uses the best known example. In it, characters are arranged on 2 scales: Good-Neutral-Evil and Lawful-Neutral-Chaotic. Players select one option from each of these scales, and combine them into their character’s alignment.

Exact interpretation of what ‘good’, ‘evil’, ‘lawful’, and ‘chaotic’ mean are up for debate beyond their broadest definitions, so you should always clarify with your DM exactly how their world interprets them. But in general, this is how I view it:

Good-Neutral-Evil Alignment

A ‘good’ character is one who always puts the wants and needs of others before their own, even at great expense to themselves. An ‘evil’ character is one who always put their wants and needs before other people’s, even at great expense to others. A neutral character will generally weigh the option, and choose the path of least expense – they’ll favor their own wants, but not if it causes too much problem for the people around them, and they’ll be happy to help provided it doesn’t take too much of a toll.

Lawful-Neutral-Chaotic Alignment

A ’lawful’ character is one who believes that following the rules, be they legal or societal, is the ideal way to exist. In general, they value safety over freedom, both for themselves and others. A ‘chaotic’ character is one who believes that the ideal way to exist is to be removed from the restriction of rules. They value freedom over safety for themselves and others. A neutral character once again falls in the middle – they’ll mostly follow the rules, unless those rules become too restrictive on their own wants, and they’re all for freedom until people start using that freedom to cause danger or harm.

Most people are True Neutral (neutral on both scales).

And that’s not a bad thing to be! But it doesn’t necessarily make for the most compelling story, or the most obvious enemies. Having Good, Evil, Lawful, and Chaotic characters and NPCs keeps things interesting in any game.

Using Alignment to Balance a Game

The current edition of DnD, 5e, doesn’t really use alignment as a true mechanic in the game. It provides a slot for it on the character sheet, and the books state that characters of certain alignments are likely to follow certain gods or use certain subclasses, but it doesn’t really enforce anything about it. Previous editions made much better use of the alignment system. Clerics, for instance, must be of an alignment within 2 steps of their god’s. After all, if you’re behaving in a way your god doesn’t approve of, they’re liable to simply remove the power that they’ve granted you. And paladins are restricted altogether. They can only be Lawful Good, and lose their abilities if they act otherwise!

While this may seem like pointless difficulty and restriction on gameplay, it actually serves as a useful balancing tool. Paladins and clerics are extremely useful classes, particularly their healing magic. But restricting the alignment of these classes also means restricting their behavior, which rules out a lot of effective tactics if you want to have them in your party. If you want heavy firepower and massive healing, you’ll just have to learn to strategize without the dirty deeds!

While 5e doesn’t officially use these rules, it’s easy enough to apply previous editions’ rules to current classes. You can find alignments associated with most spells, gods, and even prestige classes (which translate pretty easily to subclasses) in older books or online, and lend that to current rules without much fuss.

Using Alignment as a Creative Tool

Not only can alignment be useful for balancing your characters’ power, but it can also be a fun tool for bringing storytelling to life.

The Forgotten Realms, like most DnD settings, is a world of strong good, strong evil, and even stronger magic. When characters encounter entities of particularly strong moral alignment, it makes sense that they might be affected by it in one way or another.

For example, a Chaotic Evil character might need to make constitution saves in the presence of an angel. A Lawful Good character might need to make them in the presence of a lich. And they might get bonuses to their rolls while on consecrated or desecrated ground, respectively. Not only does this bring the mechanics of alignment into the storytelling, it also increases the atmosphere of great awe, dread, wildness, or order. It reminds the players that there are great forces at play, that ‘auras aren’t just a line in the rules but a powerful, evocative force of personality.

Using Alignment as a Behavioral Tool

Finally, I find that the most use I get out of alignment is not what it allows me to add to the game, but what it allows me to remove.

If I’m playing with a group of people that I don’t know well (DMing at a convention, for instance, or simply with a new group), I almost always ban evil alignments. It may sound restrictive, but I find that the practice almost entirely eliminates problem behavior.

Banning evil alignments ensures that players cannot make murder-hobo characters, cannot start fights among the party without good reason, and generally have to behave in a manner that is conducive to everyone working together and having a good time. And if players attempt to act in these ways anyway it gives me a stronger leg to stand on in stopping them. “It’s what my character would do” doesn’t hold up as an excuse when you’ve already explicitly banned characters that “would do” problematic things. And to the players it feels less like they’re being picked on, since everyone is kept from broader character creation choices, rather than allowing some versions of an evil character but not others.

Of course, playing with evil characters can be a lot of fun for both players and DMs. But new groups always have an element of surprise. And I find it best to ensure that I can enforce my decisions with the rules as well as my own judgement.

Do you use alignment in your games? Do you not? Why? Has using or not using alignment ever created any problems for you, or solved any of them? Let us know in the comments below!